This post is based on the blog post A simple explanation of how money moves around the banking system, by Richard Brown. It is mostly a restatement of the content of that post.

From the perspective of a customer, it’s tempting to think of a bank account as a ‘safe keeping’ place for your money. You give them your money, they put it in a vault (your account), and when you ask for some of it back, they go into the vault, take the money out, and give it to you.

This model is not how the bank thinks of an account, though. From a banks perspective, a more helpful model is that an account is a liability. By giving the bank money, you are lending it to them. So for the bank, an ‘account’ is just a ledger of how much you, the customer, have lent to them. The transactions on the ledger are records of you lending money to the bank (by depositing money), and reducing that lending (by drawing money). The account balance is the sum of those transactions. This is how we’re going to think of bank accounts in this post.

This means that moving money between two accounts at the same bank is trivial. If Alice instructs a payment of $10 to Bob, and they bank at the same bank, all that the bank does is make an entry on each of Alice and Bob’s ledgers. Nothing happens except a bit of bookkeeping.

Notice how this ‘nets out’: The bank owes $10 less to Alice, but owes $10 more to Bob, and the bank’s net liability has not changed.

However, this only works as long as you stay within one bank. Eventually, Alice is going to want to pay Bob $10, but Bob has an account at a different bank. How do the banks handle this?

The simplest way to deal with this is for every bank to have an account with every other bank they deal with. These are Correspondent Accounts1 1 I’m not totally sure this is the correct usage, but good enough for now. . That is, Barclays bank itself has an account at HSBC, and that account is called Barclays correspondent bank account.

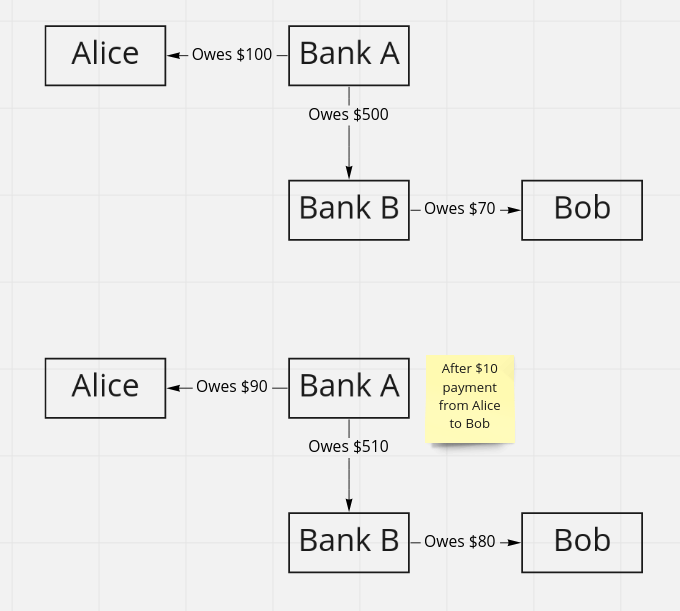

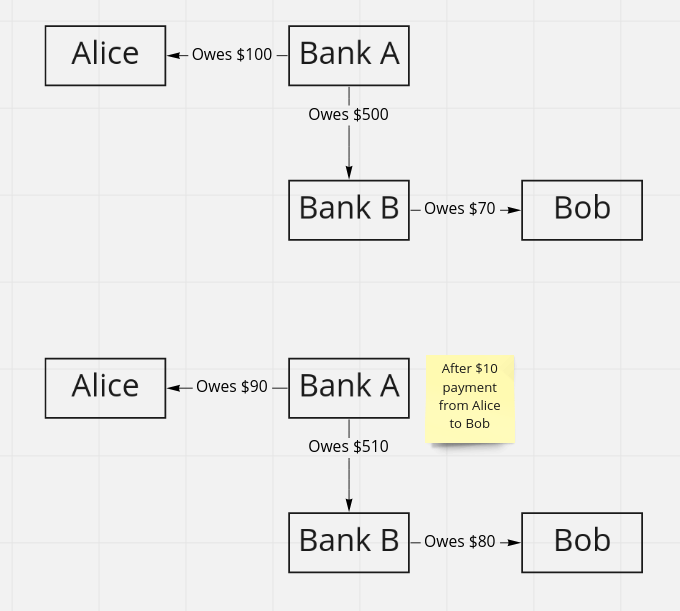

Let’s say Alice (with Bank A) wants to pay $10 to Bob (with Bank B). Bank A will reduce Alice’s ledger by $10, and increase Bank B’s correspondent account by $10. At the same time, they will send a note to Bank B saying “Hi Bank B, we increased your account with us by $10, and this is for Bob.” When they get this message, Bank B will increase Bob’s balance by $10, and will also record that they are now lending an additional $10 to Bank A2 2 Remember, a bank account represents you lending money to the bank. The same is true for correspondent accounts: A positive balance means Bank B is lending money to Bank A. . As before, the net liabilities of each bank haven’t changed. Bank A now owes $10 less to Alice, but $10 more to Bank B. Bank B owes $10 more to Bob, but is owed $10 more from Bank A.

However there is a problem with this model which make it impractical for actual use: Counterparty risk. If we repeat the above process for many transactions, Bank B will end up with a large balance with Bank A, meaning they are owed a large amount by Bank A. What if Bank A goes bust? Bank B will end up with a large mismatch between the amount they owe to their depositors on the one hand, and the amount the are owed by others. Bank B doesn’t like this!3 3 Note that there is a way around this: Since Bank A also has an account with Bank B, instead of Bank A crediting Bank B’s correspondent account, they could ask Bank B to reduce their correspondent account. This would have the effect of reducing the amount that Bank B owes to Bank A, thus preventing the build up.

A second problem is that it results in a lot of noisy communication between Bank A and Bank B if they are making thousands or millions of transactions per day, which is difficult to manage.

The solution to both of these problems is a deferred net settlement system.

In a deferred net settlement system (DNS)4 4 For example, BACS (Banker’s Automated Clearing Services) in the UK. , the banks don’t communicate about inter-bank transfers directly. Instead they send all their transactions to a central clearing system. The clearing system aggregates all of the transactions, and then at the end of the day they tot up all of the results and tell all of the banks involved how much they owe each other, and therefore how much each bank needs to credit or debit their correspondent accounts.

This eliminates the volume problem mentioned before, since each bank needs to make at most one change to the correspondent account of each other bank. It also has the benefit of being multilateral, rather than bilateral. So if Bank A needs to pay $10 to Bank B and $10 to Bank C, but Bank B needs to pay $10 to Bank C, then Bank A can make a single payment of $20 to Bank C and nothing to Bank B5 5 The article is not explicit that this is what happens, so this might not actually be true. . This helps resolve the risk exposure problem by minimizing the balances of correspondent accounts.

However, this introduces a new problem relating to counterparty risk, around timing and final settlement. If Bank A is not directly communicating with Bank B, but instead with the clearing agent, then Bank B won’t know to credit Bob’s account with $10 until the end of the day, which is problematic for efficient transfers of funds.

On the other hand, if Bank A does tell Bank B to credit Bob with $10 straight away, Bank B still won’t get the transaction ‘cleared’ until the end of the day, when the DNS system runs. If Bank A goes bust between these two times, Bank B will have mismatched liabilities again. This means Bank B has 2 options: Not credit Bob’s account until the end-of-day settlement, which has the same inefficiency problem, or to conditionally credit Bob’s account with $10, on the condition that Bank A doesn’t go bust before the end of the day. And if they do, they will reverse the $10 credit to Bob’s account. This is also problematic, because it means that Bob might “spend” the $10 that is then taken away when the credit is reversed. This lack of final settlement, as it’s called, is again a problem for efficiency, because your customers will be unwilling to spend money they don’t know is ‘final’ yet.

Most of the problems we’ve seen so far with inter-bank transfers are the result of counterparty risk: What if the bank on the other end goes bust?

A natural solution to this problem is to make sure the bank on the other end can’t go bust. Such a bank conveniently exists: The Central Bank. The idea behind a Real-time Gross Settlement system6 6 CHAPS in the UK, Target 2 in the EU, and Fedwire in the US are all examples of RTGS systems. is that banks use the Central Bank as their correspondent banker. Given that the Central Bank can never go bust (because it can always just print money), the banks can build up as much liability from it as they want.

So when Alice (at Bank A) wants to pay $10 to Bob (at Bank B), Bank A reduces Alice’s balance by $10, and tells the Central Bank to credit Bank B’s account with the Central Bank by $10. Thus, Bank B is now owed $10, not by Bank A, but by the Central Bank.

This means that the aggregation that was made a part of a DNS system to mitigate counterparty risk is no longer required. Payments are instantaneous, so the timing and final settlement problems are avoided.

You might think that we’ve solved all the problems, but one remains: cost. RTGS systems are quite expensive. I don’t know why exactly, but firstly one can imagine that the real-time nature of system means a lot of communication that isn’t necessary with a DNS System, which can be expensive. Secondly I expect it’s a function of demand and utility: A real time system with final settlement is a valuable service for customers, and banks are businesses, so they probably charge an amount that is calculated to maximize their profits.

This means that not all payments are made by RTGS. In fact, not even the majority are. For example in the UK the most commonly used payment method is the Faster Payment Service, or FPS. This is a DNS System with one critical tweak: Instead of clearing once per day, it clears several times per day. This means the time it takes to clear a transaction is significantly reduced. This is good enough for most customers, hence they don’t feel the need to shell out for RTGS unless they absolutely need the real-time settlement.

SWIFT’s role in payments is often misunderstood. It stands for the “Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication.” The “telecommunication” part is the key here. All the SWIFT network is, is a method and protocol for sending messages. It defines several standard message types for various uses.

So SWIFT is not a way to make payments. Rather it is just a way for banks to communicate with each other, and that includes the communications we’ve been talking about throughout this article.