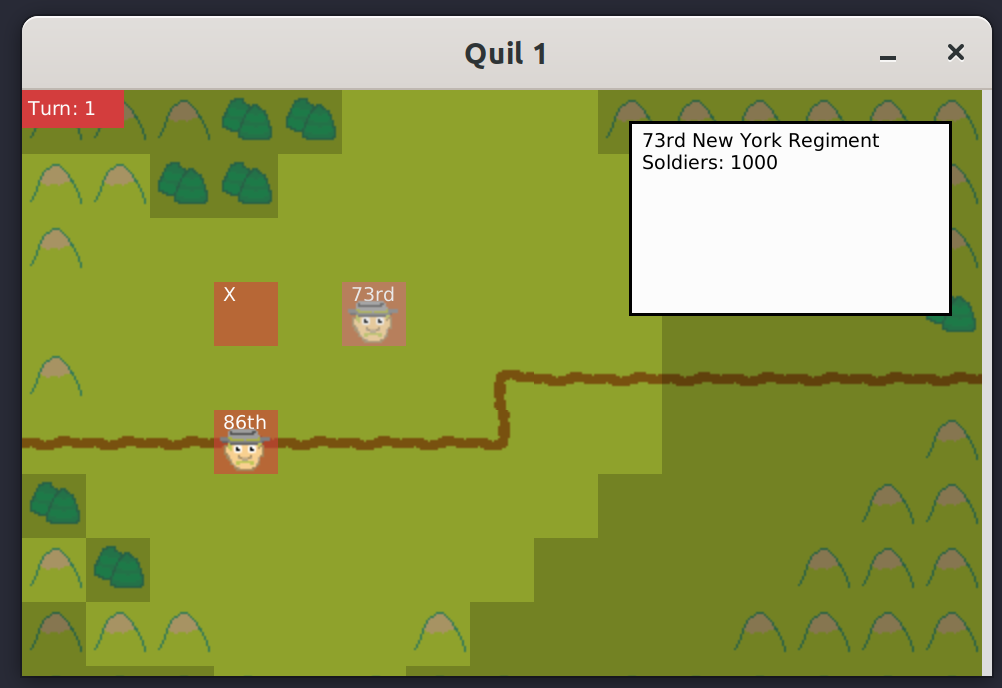

Pocket General (PG)1 1 You can see from the source it’s had a couple of names, but Pocket General is the one I’m currently going with. is a small US Civil War tactics game using Quil as a UI. PG takes inspiration from the simplicity, accessibility and retro aesthetic of the Advance Wars series for the Game Boy Advance and subsequent handhelds. However, it intends to add several elements more common in war games, such as friendly fog of war, order delay, and morale, though few of these are implemented in this version2 2 I actually had a much more advanced version of this knocking around, with some of these features, and a pretty interesting real-time dispatch system, but unfortunately it seems to have gotten lost in some migration or other. .

I wrote it to explore the different patterns and concepts used in developing a game, and to experience some of the challenges that introduces. Talking about those will be the main focus of this document. I’ve tried not to look at too much prior art, though I’ve read some articles and posts about game code.

You can launch the game from the REPL using (ui/go).

This will launch the game with a default scenario, with the red team

starting. Or, you can build the project with ./build.sh and

run the resulting uberjar, which will do the same thing.

Darker shaded squares are in ‘fog of war’, i.e. you can’t see in them. Visibility (or ‘viewsheds’, see later) are blocked by trees and hills, or extended if a unit is on a hill.

Move the cursor with the arrow keys (or wasd), and

select a unit with the space bar. This will highlight the movable area

for that unit. You can issue a move order by moving the cursor, which

will trace out a path for the unit. Note that terrain types affect

movement, with roads offering quicker transit than fields, and hills and

trees less than that. Confirm the order by hitting the space bar again,

and the unit will move.

You can end reds turn by pressing the ‘e’ key, which will mean it’s blues turn. By selecting the unit in the hills you can the effect of terrain on movement.

When you encounter an enemy unit, you can attack by moving next to them, whereupon an ‘attack’ option will become available in the menu.

From what I’ve seen, most game implementations seem to revolve around a ‘game loop’. There is a game state, and a method of transitioning this game to the next ‘tick’ of that game-state. Transitioning includes:

This happens frequently, 30 or 60 times per second. Quil implements this quite literally - here’s the slightly modified launch command, where each value is a function.

(q/defsketch game

,,,

:setup setup

:key-pressed key-handler ;; corresponds to step 1

:update tick ;; step 2

:draw draw-state ;; step 3

,,,)The fundamental elements of the game are the game-state, the handlers, the tick, and the draw.

The game state is just a map containing all the info about the game at a point in time. All the fundamental operations of the game - input handling, ticking, drawing, are functions on the game state. Here’s a significantly abbreviated map of what the gamestate looks like during a game.

{:turn-number 1,

:images ;; snip - a map of all the sprites used

:cursor [12 8],

:field {[8 8] {:grid [8 8], :terrain :field},

[11 9] {:grid [11 9], :terrain :mountains},

[7 4] {:grid [7 4], :dirs [:dr], :terrain :road},

;; snip - this goes on for a while!

}

:field-size (15 10),

:turn :blue,

:red

{:units {"c4070352-7cfa-45b7-926a-e99316830da0"

{:short-name "73rd",

:move-points 3,

:max-move-points 3,

:unit-type :infantry,

:soldiers 1000,

:movement-table {:field 1, :road 0.5, :trees 1, :mountains 2},

:move-over false,

:viewshed #{[8 8] ;; and other coordinates

},

:id "c4070352-7cfa-45b7-926a-e99316830da0",

:side :red,

:unit-name "73rd New York Regiment",

:position [8 4]}}}

:blue {:units ;; other units

}

:camera [0 0],

:ticks 27383,

:order-queue ()}The UI library is Quil. The UI namespace itself contains any calls to

the Quil API, with domain specific functions like

draw-attack-cursor, draw-unit,

draw-menu, as well as more generic draw functions which

mostly compose these - draw-sprite,

draw-tile.

The main function of the UI namespace is

draw-state :: game-state

(defn draw-state [game-state]

(let [{:keys [images camera]} (layers/constants game-state)]

(draw-terrain (layers/field-layer game-state) images camera)

(draw-units (layers/unit-layer game-state) camera)

(draw-intel (layers/intel-layer game-state) camera)

(draw-highlights (layers/highlight-layer game-state) camera)

;; etc. for other layers

))The draw-state comprises several more specific function, each of

which successively draws a ‘layer’ of the game state, starting with the

terrain, then the units, etc. In this way, modifications to different

elements of the UI are effectively decoupled for change, and the system

is extensible to new elements by adding new layers. Additionally, the

drawing functions are decoupled from the game-state implementation

itself via the layers name-space, which provides functions

to filter and format information from the game state relevant to that

layer. Some of these are simple pass-throughs, like

(defn highlight-layer [game-state] (:highlight game-state)).

Some have some logic in them, such as this one, which limits the units

which are passed to the UI to draw to those which belong to the player,

or which are in the players line of sight.

(defn unit-layer [game-state]

(let [my-side (:turn game-state)

my-units (forces/units game-state my-side)

viewsheds (or (vs/all-viewsheds game-state) #{})

visible-enemy-units (filter #(viewsheds (:position %)) (forces/units game-state (other-side my-side)))]

(concat my-units visible-enemy-units)))One concept that I hadn’t heard of before I worked on this was the Bresenham Algorithms. Often when you want to draw something, you find yourself working in a continuous vector space, and need to transfer this to a discrete vector space - for example, a screen made of pixels. Let’s say you want to draw a line on a pixelated screen. If the line is perfectly horizontal or vertical, no problem. But if the line is diagonal, how do you figure out which pixels you need to shade? This problem obviously extends to any shape made of straight lines, but also circles, which is relevant to the game.

This is the problem that Bresenham’s algorithm (in line and circle variants) solves. I won’t go into how the algorithm works, but it becomes necessary in the game for calculating how far a unit can see around them (“viewsheds”) A unit can see around them in all directions to ‘x’ spaces. To calculate this, you say a unit can see around them in a circle of radius 5. Bresenham’s circle algorithm will determine the ‘edges’ of the circle. Bresenhams’ line algorithm will draw a ‘path’ from the unit to each coordinate on the edge of the circle. The resultant set of coordinates are the things the unit can see, aka it’s viewshed.

(draw-points (bresenham-circle [5 5] 4))

[. . # # # # # . .]

[. # . . . . . # .]

[# . . . . . . . #]

[# . . . . . . . #]

[# . . . U . . . #]

[# . . . . . . . #]

[# . . . . . . . #]

[. # . . . . . # .]

[. . # # # # # . .]

;; from viewshed namespace

(defn paths [n loc]

(let [edges (set (br/bresenham-circle loc n))]

(for [point edges]

(rest (br/bresenham-line loc point)))))You do need to make some line-of-sight adjustments though. For example, a tree tile is not in a unit’s viewshed unless they are standing right next to it, and they also block sight of any tiles behind the trees. Mountains are similar in that they block line of sight, though the mountain itself is included in the viewshed. Lastly, if a unit is standing on a mountain, the radius of the viewshed is increased. Each path is ‘walked’ to account for any terrain effects:

(defn walk-path [path loc tile-terrain]

(reduce (fn [out-path next-tile]

(case (get tile-terrain next-tile)

:trees (reduced (if (and (adjacent? loc next-tile) (empty? out-path))

[next-tile]

out-path))

:mountains (reduced (conj out-path next-tile))

(conj out-path next-tile)))

[]

path))The game loop is premised on an order system. Orders are issued to

units, and a queue of these orders is stored in the game state. A ‘game

tick’ is, in effect, just the processing of the next order in the queue,

implemented in the (poorly named) inputs namespace. If

there’s a current order, execute it (by a switch conditional on the

order type). If there’s no current order, but there are order on the

order queue, promote the head of the order queue to the current order.

If there are no orders, do nothing - this function should only be called

when there are orders in the queue.

;; in inputs namespace

(defn execute-next-order [game-state]

(cond (:current-order game-state)

(let [[order-type side unit target] (:current-order game-state)]

(case order-type

:move (execute-move-order game-state order-type side unit target)

:retreat (execute-move-order game-state order-type side unit target)

:attack (execute-attack-order game-state side unit target))

:end-turn (end-turn game-state side))

(not-empty (:order-queue game-state))

(-> game-state

(assoc :current-order (first (:order-queue game-state)))

(update :order-queue rest))

:else (do (println "Erroneous input handle")

game-state)))(Note that ‘end turn’ is implemented as an order-type, along with move, retreat and attack, which conflates two things. This is poor design and should be fixed.)

An “order” is a tuple of type + side + id + x, where

x is dependent on the type of order. For example a Move

order would look like

[:move :red :unit-a ([1 1] [1 2] [1 3])], where the last

element is the route the unit is planning to take. (Attack orders and

combat I’ll talk about separately.)

The order queue is intended to be a mechanism for decoupling what a unit is doing from the source of what asked them to do it. Examples of what can ‘make’ a unit do something are:

Once an order is issued it doesn’t matter how it originated, it’ll get executed just the same.

Orders represent an order a unit has received. However, communication on a battlefield is not instantaneous. A commanding unit sends a dispatch to a subordinate unit. These systems are modeled separately in the game, for the following reasons: